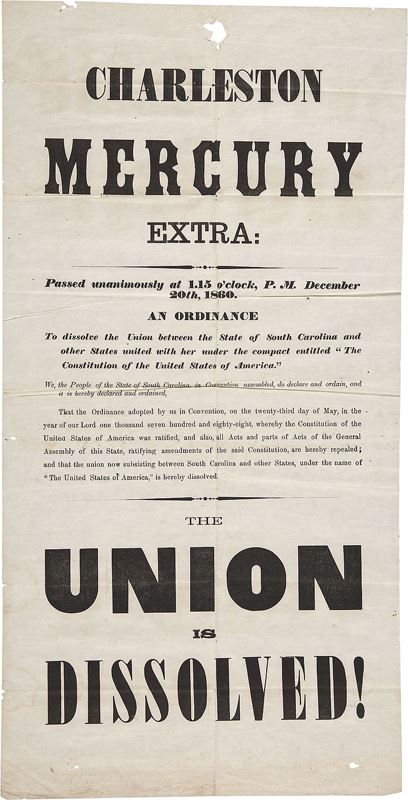

The economic history of the American Civil War concerns the financing of the Union and Confederate war efforts from 1861 to 1865, and the economic impact of the war.

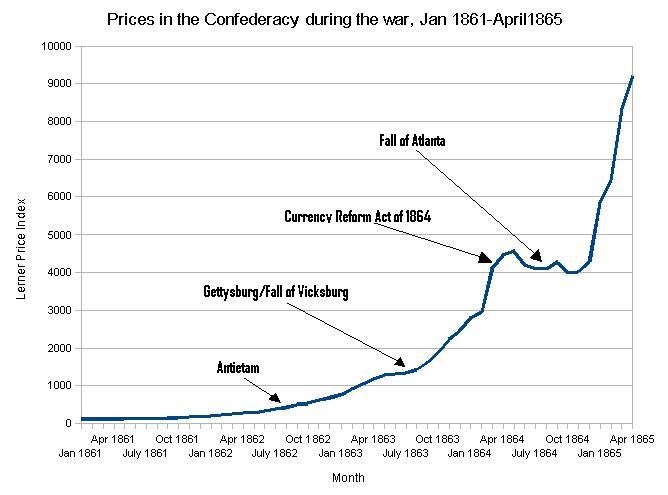

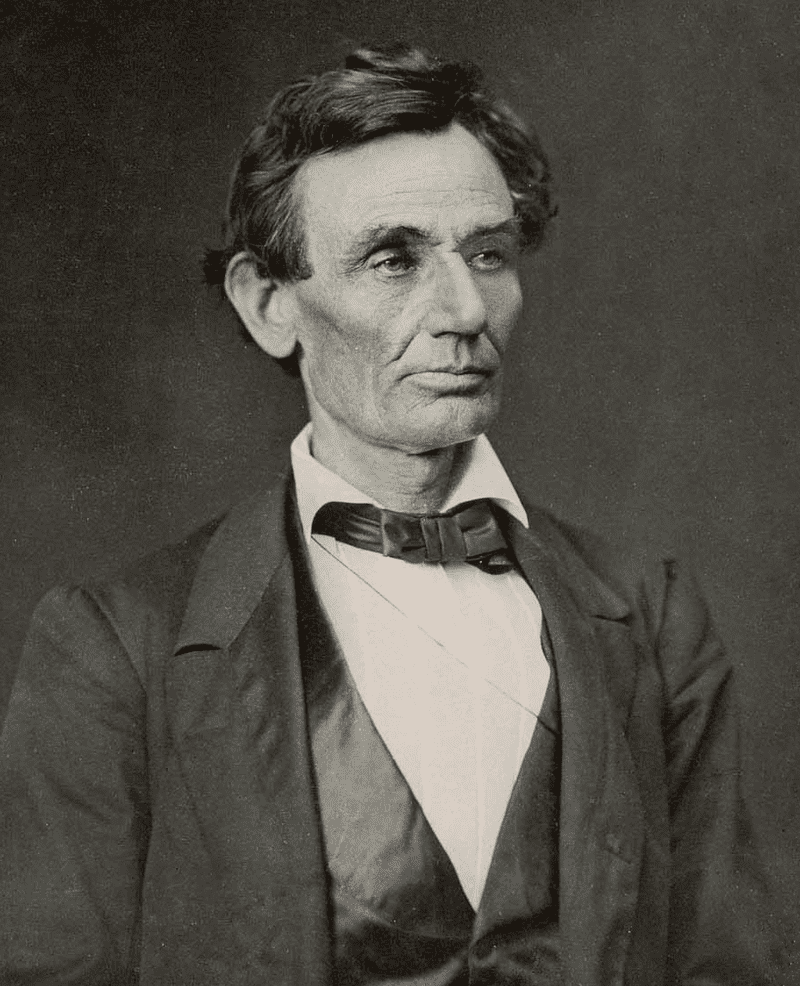

The Union economy grew and prospered during the war while fielding a very large Union Army and Union Navy.[1] The Republican Party in Washington, D.C. had a Whiggish vision of an industrialized country, with great cities, efficient factories, productive farms, all national banks, all knit together by a modern railroad system, to be mobilized by the United States Military Railroad. The Southern United States had resisted policies such as tariffs to promote industry and the Homestead Acts to promote farming, because slavery in the United States would not benefit. With the South gone and the Northern Democratic Party weak, the Republicans enacted their legislation. At the same time, they passed new taxes to pay for part of the war and issued large amounts of bonds to pay for most of the rest. Economic historians attribute the remainder of the cost of the war to inflation. According to Matthew Gallman, In terms of total war spending, the federal government of the United States spent $1.8 billion and the U.S. states spent $0.5 billion. This does not count long-term costs after the war ended, such as veterans’ benefits. The Confederate federal and state governments spent the equivalent of $1.0 billion in US dollars. The US obtained 21% of the war funding from taxation, 66% from borrowing, and 13% from inflation. By contrast, the Confederacy obtained only 5% from taxation, 35% from borrowing, and 60% from inflation.[2]

In Washington, D.C., the United States Congress wrote an elaborate program of economic modernization that had the dual purpose of winning the war and permanently transforming the economy.[3]

The wartime devastation of the South was great and poverty ensued; the incomes of White Americans dropped, but income of the freedmen rose. During Reconstruction, railroad construction was heavily subsidized (with much corruption), but the region maintained its dependence on cotton production. Freedmen became wage laborers, tenant farmers, or sharecroppers. They were joined by many Poor Whites, as the population grew faster than the economy. As late as 1940, the only significant manufacturing industries were textile mills (mostly in the upland Carolinas) and some steelmaking in Alabama.[4][5]

The industrial advantages of the North over the South helped secure a Northern victory in the American Civil War (1861–1865). The Northern victory sealed the destiny of the nation and its economic system. The slave-labor system was abolished; sharecropping emerged and replaced slavery to supply the labor needed for cotton production, but cotton prices plunged during the Panic of 1873, leading the plantation complexes in the Southern United States to decline in profitability. Northern industry, which had expanded rapidly before and during the war, surged ahead. Industrialists came to dominate many aspects of the nation’s life, including social and political affairs.